Matthew 5:38-48

38 “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.’ 39 But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. 40 And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. 41 If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. 42 Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.

43 “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ 44 But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, 45 that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. 46 If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? 47 And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? 48 Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

This is the part of the sermon of the mount which is, at the same time, the most admired and least obeyed section of the whole sermon. Indeed, perhaps of the whole Bible.

Almost every thoughtful person has admired the teachings of Jesus here. But how few there are that are actually obey His words. In fact, there are not a few who have just decided that his commands are too high and unrealistic. Some preachers even go so far as to tell us that we are not to actually obey them now; they are for heaven or the millennium.

Are they right, or are they totally and tragically missing the whole point of what Jesus is saying? Well, to answer this, let’s first spend some time actually looking at what Jesus says. Is He, for example, telling us not to use self-defense or to go to war? After all, I have heard people uses these verses to argue against the death penalty or joining the military or the police. Are they right?

This section breaks into two parts, which each begin with Jesus quoting the old standard of righteousness, and then Him giving a new standard, the standard of the kingdom of God.

He begins with the idea of retribution or revenge. You have heard it said, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”. Now, where was this said? In the Old Testament. It is in a section of legal commands; when a court finds someone guilty of theft or injury, they were to exact a judgment equivalent to the offense.

This actually was intended as an act of mercy, of sorts. The goal was to limit the damage and de-escalate the feud. Say I injured you or someone in your family in some way; it might be a physical injury, a theft, or something to injure your family’s honor. Almost certainly someone from your family would seek to get back at me by injuring me in some way, and usually beyond the original injury. They would escalate it, partly to dissuade it from happening again, and partly just out of human sin and grievance. So what would I and my family or clan do about that? We would then respond to that injury, usually by an escalation of our own. Which would lead to…well you get the picture.

The law of eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth, then, was not intended to command revenge but to limit punishments and de-escalate conflicts. In practice, however, people being people, it often was used as a justification for personal revenge. So, while the Old Testament did indeed include the idea of eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth, the idea was seriously abused in the popular understanding.

Jesus then gives the way of the kingdom regarding someone who has hurt us. You can sum it up very easily and very simply. Jesus’s commands are never hard to understand, however hard they are to do. He simply says, do not resist a person who harms you.

He then gives four illustrations of this principle, showing how to respond to people who hurt us in various situations. I emphasize: these are illustrations, not commands. They show what the principle means, not give some sort of exhaustive application of the principle.

The first situation is when someone insults you. That is actually what Jesus means when he talks about someone striking us on the right cheek. 90 percent of people are right handed, and so to slap someone on the right cheek would mean a backhanded slap, not a fist to the jaw. And in that world it was a degrading insult, something like giving someone the middle finger today.

And you know, its good for us to realize this, for we are going to face a LOT more people insulting us than actually physically hurting us. I can’t recall a time since 8th grade when I actually got slugged by someone. But I can think of dozens of times I have been insulted in large or small ways.

What do we do?

Instead of slapping them back, or worse, we turn our face and offer the other cheek for them to slap also. Or, to put it in modern terms, we refrain from responding with insult to insult, with snark to snark, with sarcasm with sarcasm, to snide remark with snide remark. Instead, we allow them to think about us, and talk about us, as they want to. Yes, even on FaceBook.

The second illustration is a legal one: if someone sues you to take away your tunic, give him your cloak as well. A tunic was, of course, your standard garment or robe, while your cloak was something of a loose jacket. Jesus imagines a situation where in some sort of dispute someone has some sort of claim against you, perhaps in a legal sense, and, instead of doing all you can to win, you do all you can to help that person, even giving them more than what they asked for legally if they need it.

The third illustration will seem odd to us: if someone forces you to go one mile with them. Now, who would force us to walk with them a mile? This seems strange to us. But Jesus’ audience would know exactly what He was referring to. All of Israel was under Roman occupation. Soldiers would be stationed in every town. And, by law, any of these soldiers could force any citizen to carry their pack for them, with the distance limited to one mile. Now, of course, this rule was hated by the Jews or any citizens. Not only was the pack heavy, and the time likely inconvenient, but also it very graphically reminded them that they were under the yoke, the burden of Roman rule.

So this is a situation where someone in authority demands that we do something that we don’t want to do. And the response we are to have is to actually do more than what is asked, instead of meeting that command with a surely and angry attitude, doing the bare minimum needed to avoid unpleasant consequences.

The last illustration Jesus uses here is that of someone who wants something of our possessions, either to borrow it or simply to have it. And we are told to give to the one who asks, and not to avoid those who want to borrow from us. This one does not require any cultural unpacking. We will have people who will seek to borrow from us or to ask us for money or things.

What do we do? We give, without worrying about two things that we normally worry about when we make the decision to give or lend. First, whether they will repay; second, whether they have any claim upon me. What I mean is that if they have shown kindness to me, or if they are my family or church or race, I may be more likely to give than if they are not. Or if they have some other attribute that I like or find admirable, I may be more likely to give. But in the kingdom we are not to let our giving be determined by who they are or what they have done or whether it’s likely we will get paid back or helped in some other way. The only thing that determines our giving is love.

Does that mean we should give to every person begging on the streets, or financially support the bad decisions of a relative? No. Because love is giving to meet the true needs of the other person, not simply their desires. If I determine that it is likely that my giving will not help that person’s true need, but instead will keep them from getting a better kind of help, then the loving thing to do is withhold my giving. Now that is not always easy to know. Which is why these are not rules Jesus lays down to us, that we are to follow at all times. They are illustrations showing us what love looks like toward other people in the kingdom.

The last section of chapter five flows from this, in a sense. It is about loving our enemies. You have heard, Jesus says, that you are to love your neighbor and hate your enemies. Now, is that command from the Old Testament? No. Only the first half. The Old Testament nowhere says we should hate our enemies. In fact, there are commands like this: “If you find your enemy’s ram gone astray, take it back to them”. But again, to our fallen human nature, the idea of hating our enemies seems so legitimate and right that it very naturally came to be attached in people’s minds and teachings to the command to love one’s neighbor.

Jesus again teaches us another way. “I say to you, Love your enemies, and pray for those who hurt you”. And, obviously the context means we pray for their good, not for a fireball from the sky to land on them.

Let’s note a couple things about this.

First, we are likely going to get the wrong idea about this, if we don’t remember that “love” in the Bible means something different than “love” in our culture. For us, love is primarily an emotion; It is how I feel about someone or something. In the Bible, love is primarily an action; it is not only that, of course. It is also an emotion. But, especially when used as a command, it has the idea of actually doing something, like the parallel phrase “do good to those who persecute you”. We are not being commanded to have a certain emotional affection to our enemies or to those who have hurt us or are hurting us. We are being commanded to do good to them. To pray for their good, to seek to help them, if possible, and to refuse to hurt them.

Now, note the reason. Is it because they deserve it? No. Is it just because it is the nice thing to do? No. The motive is this: you will become children of Your father in heaven. He sends the life-giving sun, and the refreshing rain, on the good and the bad, the righteous and the unrighteous.

To be the son of God has two aspects: relationship and likeness. In terms of relationship, we are already son or daughters of God by his grace; but in biblical times and in biblical thought, to be a son of someone was to do the same things that someone else was doing. And clearly that is what Jesus has in mind: this is what God does; be like Him.

Anything less than this means basically falling to the level of behavior of those who don’t even know God. If you love those who love you…what are you doing more than the tax collectors (regarded as the worst sinners)? If you give honor and greeting only to your brothers, the people like you, what are you doing more than the Gentiles (those who don’t know God) doing?

What Jesus is emphatically rejecting here by these words is not just getting back at our enemies or people who hurt us, but the tribalism that guides so much of our behavior. By tribalism I mean the unceasing human tendency to form tribes of people that we belong to, that we attach ourselves to, and find our value in.

In the ancient world, this was literally a tribe, or a subset of a tribe. The basic family unit was the family, which would include grandparents and cousins. Then the clan, which would include more distant relations. Then the tribe, which for Israel meant one of the 12 tribes descended from Jacob and his wives. And then, above them, was the nation.

We don’t have that structure today, for the most part. But the principle of tribalism has many forms; one is nationalism, the feeling that our nation is superior to all others, and that what happens to us is more important than what happens to them. Another form of tribalism is political: an overly strong attachment to our political party, to the point where we evaluate and even value people based on whether they are a Republican or Democrat. Obviously race is a big one in our culture. For us Christians, it may take the form of viewing with suspicion or dislike those who are gay, transsexual, or transgress traditional morality. And, of course, religion can become a tribe in this sense also.

We are called to do good, and pray for good, toward those who hurt us, or those who are simply not in our tribe.

And what if the other people don’t do the same for us? What if they malign us or insult us? Then we need to ask ourselves very honestly if we want to be like those people or be like God.

Now, how can we put this into practice? I would suggest two things.

First, ask God to open your eyes. Ask Him to help you see what He sees in other people. On our own, we too often see and evaluate others on criteria that is both outward and self-focused. What I mean by self-focused is that our own interests and values are in focus as we think about both the value and the needs of the other person. Have they done me good, or ill? Do they look like me? Think like me? Worship like me? Vote like me? We need help to see the inherent and eternal worth in the other person.

Second, do what you can, not what you can’t. This is a good rule in many areas of life. Can we live up to the words and example of Jesus every day and every way? No. Can we live up to them more tomorrow than we did yesterday? That is the real question, and the answer is obvious.

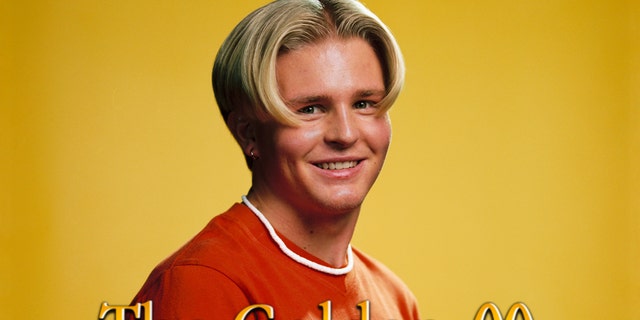

Toy Story came out 25 years ago

Toy Story came out 25 years ago

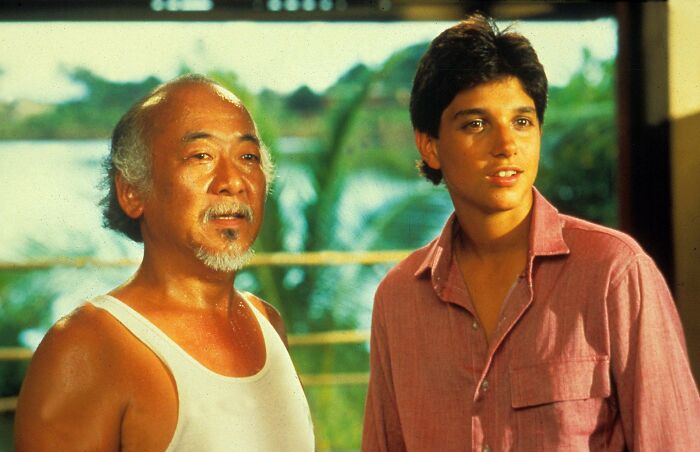

Ralph Macchio, the actor who played Daniel LaRusso, is now older than Mr. Miyagi was when Karate Kid came out

Ralph Macchio, the actor who played Daniel LaRusso, is now older than Mr. Miyagi was when Karate Kid came out